Dutch sales of German military trucks to Sudan ended up in Kordofan conflict

In June 2015 Dutch Radio1 programme Bureau Buitenland broke the story of military trucks that had been supplied to Sudan by Van Vliet Trucks Holland BV. While they were officially delivered as ‘demilitarised’ and to a private company, the very same trucks had been captured from Sudan’s armed forces (SAF) by SPLM-N rebels in South Kordofan. Nearly a year later, in response to that case, the Dutch government has now changed its policy, requiring a licence for the export of former military vehicles – demilitarised or not.

By Frank Slijper

PAX assisted in the investigation for the radio programme. Much of the research focused on the key question: how could surplus German military trucks, sold to a private Dutch company turn up with the armed forces of a country under a full EU arms embargo, led by a president indicted by the International Criminal Court?

While her ministry long insisted that nothing was wrong with the truck deals (“demilitarised + commercial destination = legal”), in early September, under parliamentary pressure, Dutch Foreign Trade minister Lilianne Ploumen admitted that she was very unhappy with the case and announced measures to prevent similar cases from happening in the future.

The story originated from a 2013 report by Swiss-based Small Arms Survey (SAS), detailing how MAN military trucks, shipped from Europe in 2010 and 2011, were seen in South Kordofan. The trucks had been captured from Sudan’s army by fighters from the SPLM-N (Sudan People’s Liberation Movement – North).

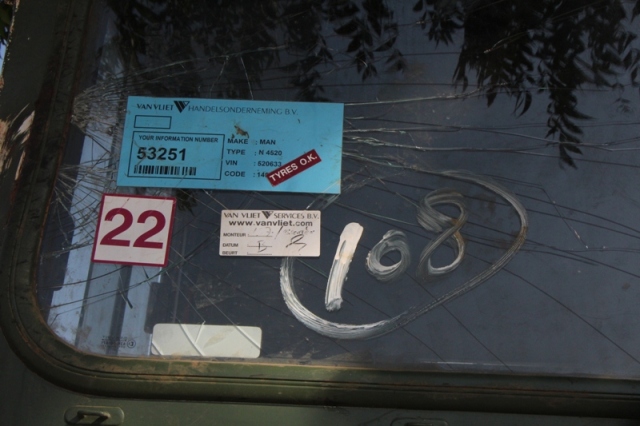

Labels still visible on the trucks revealed that Van Vliet had supplied the trucks, which they had previously bought from VEBEG, a part of Germany’s Ministry of Finance that manages sales of Bundeswehr surplus stockpiles. The trucks were shipped from Antwerp on 26 June 2010 (4×4 type) and from Amsterdam on 27 October 2011 (6×6 type). One shipment offloaded in Port Sudan contained 99 ex-military trucks. Dutch authorities and Van Vliet so far have not revealed the volume of the second shipment, nor any other transfers of ex-military equipment to the region.

The official destination of the trucks was Concept Development Co. Ltd., a company registered in Sudan’s capital Khartoum. According to the SAS research the company’s address is the same as Giad Services and Investment Co. Ltd—likely to be part of GIAD Holding, which is directly controlled by the Sudanese government and known as one of Africa’s main producers of military vehicles. The company was the subject of investigation by UN experts and others for breaches of the Darfur arms embargo, and has been sanctioned by the US Treasury.

This certainly wasn’t the first Dutch controversy around the export of military trucks to conflict areas. In 1992 military trucks turned up with forces fighting for newly independent Croatia. After a last-minute buy-back deal in 1997, 150 military trucks waiting in Vlissingen were prevented from being shipped to then-Zaire’s dictator Mobutu. Soon after, Dutch authorities announced to apply stricter rules to 4WD truck exports, which “can have military-strategic value” when supplied in “significant quantities”. Similar measures were again announced in 2008, but they only applied to trucks sold from Dutch military stocks. That loophole thus re-emerged just a few years later when Van Vliet sent the ex-German trucks to Sudan. While both Van Vliet and The Hague kept emphasizing that the trucks were ‘demilitarised’ and the export was therefore perfectly legal, it was clear they missed the whole point of what is at stake: military relevance and military use combined with embargoed or otherwise controversial destinations.

At least four captured Van Vliet-supplied trucks have been identified at the front line in South Kordofan, with company stickers still on the front window, as photographic evidence shows . The trucks are used for transport of troops and to supply arms and ammunition and thus strategically important to the SAF. According to the SPLA-N some 70 trucks have been captured from the SAF since war resumed in 2011.

Moreover, one Van Vliet truck was found with Seleka rebels fighting in the Central African Republic, investigations by Conflict Armament Research revealed. It has not been established how it got there, nor how many more are in that country.

As a consequence of our research into Van Vliet trucks, a German lawmaker raised the issue, and in answer to parliamentary questions Germany introduced new measures. It since requires foreign trading companies to ask permission from Germany whenever they resell equipment bought through VEBEG and to show an end-user certificate, regardless whether authorities in the trader’s country would require a permit for such exports.

Van Vliet itself should have known that exports of such trucks to Sudan, regardless of being ‘demilitarised’, are sensitive and could end up being used in conflict, especially since the company is no stranger to Sudan. It was the only country for which it had a special export manager – at least until June 2015. In June Van Vliet said it was ceasing its business with Sudan as a consequence of all media attention, and for fear of US sanctions.

The good news is that, in a message to potential exporters, the Dutch government says it has adapted its policy, requiring a licence for the export of former army vehicles if they were originally designed for military purposes. In fact they cannot be demilitarised anymore from an export control point of view.

Of course this is a very welcome measure taken, closing a loophole in Dutch arms export control. As European governments often struggle to implement common rules, it is important that The Hague ensures that European colleagues maintain the same standards to control the surplus military vehicle trade.