Fighting together for peace

World War II is still raging, centuries-old cities lay in ruins and thousands of young people are dying on the battlefield every day. The French bishop Pierre-Marie Théas is in detention. He offended the Nazis by criticizing the deportation of the Jews. As he sits in a Nazi prison, he repeats that one phrase from the Bible: “Love your enemies”. Quite a brave thing to say in a cell block full of prisoners desperate to kill their enemies. The fury he sees all around him makes him realise how difficult it will be, once the fighting stops, to reconcile the arch-enemies France and Germany. But there is no other way to achieve a lasting peace.

Théas is released and comes into contact with the French teacher Marthe Dortel-Claudot, whose thinking is compatible with his own. Like many others, they are fed up with war. They want reconciliation rather than retribution, to bring people together rather than set them against one another. They join up to found Pax Christi. The movement grows fast. In 1949, 25,000 young people from 34 different countries, including many from Germany, gather at Lourdes. People who had until recently been trying to kill one another are now looking for a way to deal with the past. Reconciliation between France and Germany also becomes a political, European project. Western Europe has been free from war ever since.

Peace movement extends round the world

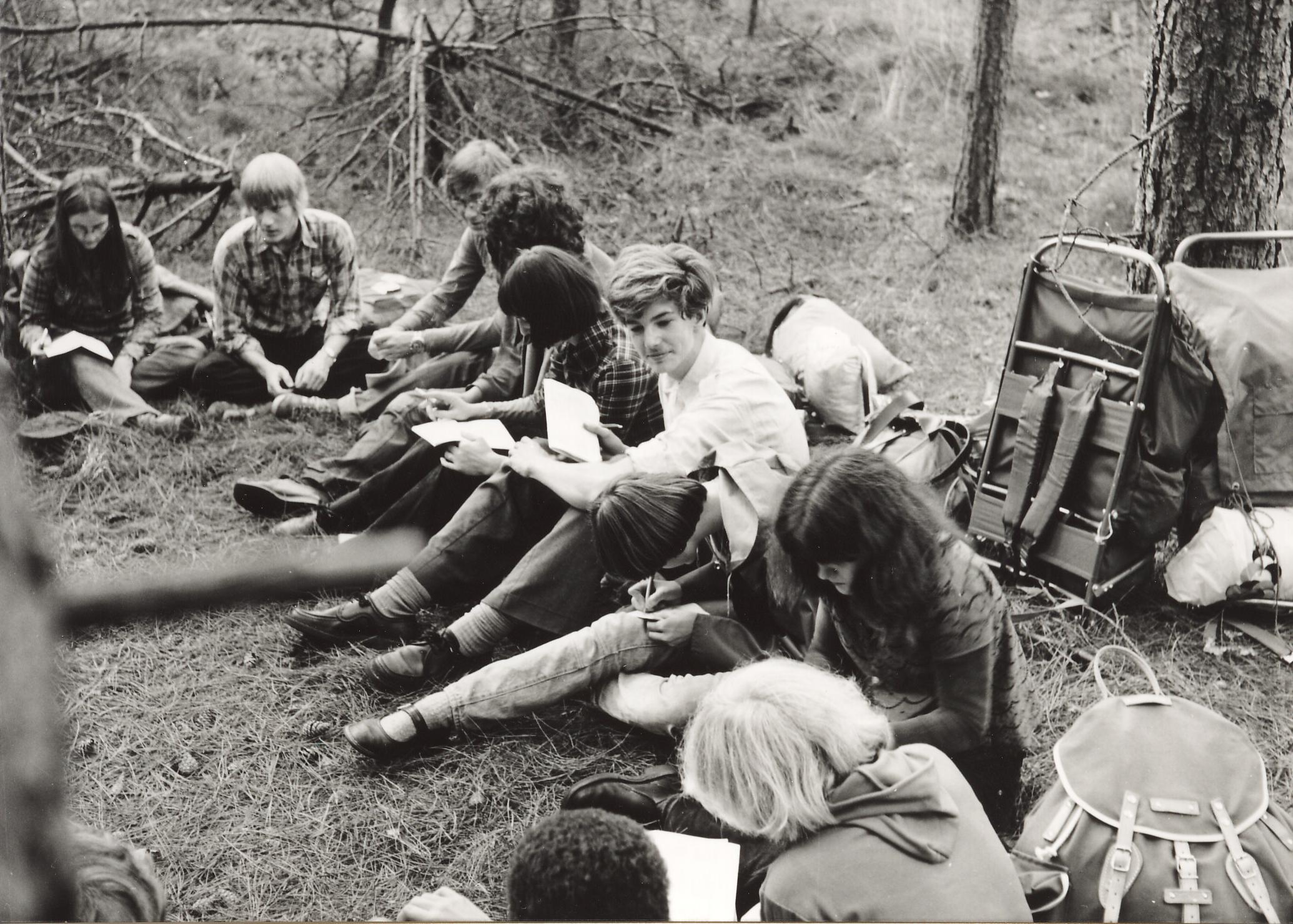

It is the beginning of the 1960s and the tone is different. The Beatles bring about a new kind of liberation, love and peace are in the air. But the hope brought by people like the Beatles and Martin Luther King is squashed. In Vietnam, a war rages and inhumane weapons that do not discriminate between civilians and soldiers are used. Napalm is dropped on entire villages, on civilians, leaving a scorched earth in its wake. In Europe, the Cold War is felt everywhere. An Iron Curtain divides Europe into East and West. People cannot travel freely. Pax Christi organises marches, people walk for days on end while they discuss the meaning of peace. But these marches never cross the border into Eastern Europe. The walks are important in generating understanding and solidarity. But what happens when they run into walls, barbed wire and soldiers?

Time for change, for a broader approach. The people of Pax Christi start to use means other than prayer and dialogue. Increasingly, they conduct their own research into conflicts and how to resolve them. The establishment of IKV (the Inter-church Peace Council) creates an ecumenical sister organisation alongside the Catholic Pax Christi. For both, the Iron Curtain is a thorn in their side. There is well-established contact with dissidents in the East, who later become the leaders of their counties. When the US deploys nuclear weapons in the Netherlands and the arms race seems unstoppable, it is time for action. “Help rid the world of nuclear weapons, starting with the Netherlands!” is IKV’s slogan in the late 1970s. There are protests. They are organised with increasing frequency and on an ever-growing scale, with IKV’s Mient Jan Faber as the face of the demonstrations. In 1983, 550,000 demonstrators gather in The Hague for what will later be considered a historic event. To this day, It is still the largest protest march ever held in the Netherlands.

The two peace organisations are asked by people in other parts of the world to become involved in their local activities. Important relationships with partners are established in the Middle East, Africa and South America. Regions where conflicts pit groups against one another and where it is so important to work on reconciliation after of the violence stops. IKV and Pax Christi increase their collaboration, and the two become one. The new organization focuses on the European countries behind the Iron Curtain in an effort to assuage the tense political relations. The fall of the Wall and subsequent cooperation are due in part to that work. Peace agreements are signed in both South Sudan and Colombia. IKV-Pax Christi holds major companies to account that had played a dubious role during conflicts. An example is the oil company Lundin, which after years of IKV-Pax Christi investigations is tried for complicity in war crimes against humanity in Sudan.

New generation, new solutions

In 2006, Pax Christi and IKV join forces permanently and together they create PAX. A new generation of peace-workers rises and fights for peace alongside PAX veterans. We still organize protest marches, but much work now takes place in collaboration with local partners or large institutions such as the United Nations. One of our major triumphs is the UN treaty for the prohibition of nuclear weapons, adopted by 122 countries. This resulted in the Nobel Peace Prize in 2017 for ICAN, the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons, in which PAX is closely involved. We are also working hard to get banks, insurance companies and pension funds to stop investing in companies involved in making controversial weapons.

So here we are, as PAX. With our compassion for people and our opposition to injustice, amid the reality of gruesome conflicts, political games, financial interests and social exclusion. A grim reality in which innocent civilians all too often become the victims. We investigate the violence in Syria, offer legal assistance to the victims of blood coal in Colombia and arrange for Dutchbat soldiers to meet the women of Srebrenica.

.jpg)

So here we are, as PAX. All our research has made us experts but we remain activists, prepared to mount the barricades. We are political advocates who serve as the conscience of major companies. We are at the same time older and wiser, but also youthful and bursting with energy and optimism.

Safeguard, stop, stimulate

The broadening of our scope that began in the 1960s has taken us in many directions. We are many things. So a little more focus would not hurt. Accordingly, three issues are at the forefront of our work. Three words that all start with S: safeguarding civilians against the violence of war, stopping armed conflict and stimulating peaceful and just societies.

Safeguarding civilians… you cannot always stop wars, but you can prevent arms trade with countries that violate human rights. Measure weapons against the laws of war and ban controversial weapons so as to minimise the number of civilian casualties. Stop the use of explosive weapons in villages and cities. Fight against the cluster bombs and nuclear weapons of today and the killer robots of tomorrow. PAX also trains soldiers in the protection of civilians during times of war.

Stopping armed conflict… this is something we cannot do alone. We draw attention to conflicts, lobbying here in the Netherlands and internationally. Governments should act on the basis of the right values and put human dignity at the top of their priority list. They also need to be aware of the power they have. The Netherlands trades a great deal, including with countries where things are not as they should be. We call for that economic power to be deployed for the improvement of human rights and ending conflicts.

Stimulating peaceful societies… starting a dialogue between sworn enemies works, as does learning how to deal with the past. PAX can trace this approach back to our founding, when we worked with the Germans and French after the Second World War. Nowadays, we use a similar approach in Africa, the Middle East, South America and Central and Eastern Europe. In places where violence is raging or just recently stopped. We also work for solidarity here in the Netherlands, where we cooperate with committed citizens across the country. This work comes to life in the annual Peace Week in September. We receive funding from donors, foundations, and government bodies that believe in the work that we do.

Supporting others

PAX aims to demonstrate courage and leadership both now and in the future, just as Bishop Théas, Mient Jan Faber and all those others did in the past. That is what PAX aims to be, an adventurous leader that shows peace is possible. Of course there will be new conflicts, and possibly new wars too. We are not naive — no peace organisation can afford to be. Sometimes the period of peace after years of war is brief. But it is precisely during that brief period when people learn what it is like to live together in peace, and why it is so important to fight for peace. It is just such moments which give us the hope to keep going. That is why PAX stands with people who strive toward peace, both during conflict and afterwards. We want to amplify their voice and increase their political power. Everywhere, people are working towards peaceful, inclusive societies. Amid violence, they bravely fight for peace. That takes courage. They keep going, stubbornly, against all odds. And we stand by them.